The Light and Dark of Love: A Reflection on Another Marvelous Thing

Laurie Colwin’s Another Marvelous Thing is one of those rare books that feels startlingly modern despite its modest, almost understated prose. Written in what feels like interconnected vignettes (while maintaining a cohesive narrative), the book chronicles the affair between Billy and the older Francis, a man whose restlessness is both charming and, at times, exasperating. Yet, to read it as a critique of infidelity is to miss the point entirely. Colwin doesn’t moralize. Instead, she dives into the messiness of human relationships with compassion and clarity, exploring the spaces between desire and expectation, light and dark.

This passage, in particular, stood out to me:

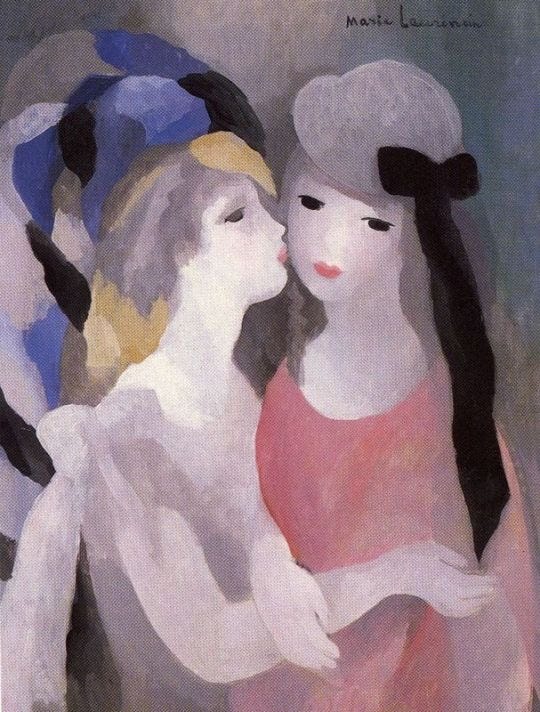

"And yet, he thought, as he gazed at the top of Billy's head, at his age a man required a little light and dark—a little something that made the images of life as clear and startling as those on a photographic plate."

Francis’s reflection reveals a central truth of the book: our human need for contrast, for complexity, for the paradoxical tension between what is steady and what disrupts. His affair with Billy isn’t about a lack of love for his wife or a desire to destroy his marriage. It’s about something deeper—something both selfish and universal.

At its core, Another Marvelous Thing is a meditation on the impossibility of one person fulfilling all our needs. Romantic love, as we've been taught to understand it, demands so much. We expect a partner to be a lover, a confidant, a co-parent, a financial partner, a cheerleader, a therapist, and, somehow, the answer to all our existential longing. It’s an impossible ask, yet it’s baked into the cultural narrative of love as completion. Colwin’s brilliance lies in her ability to unspool this narrative without casting judgment.

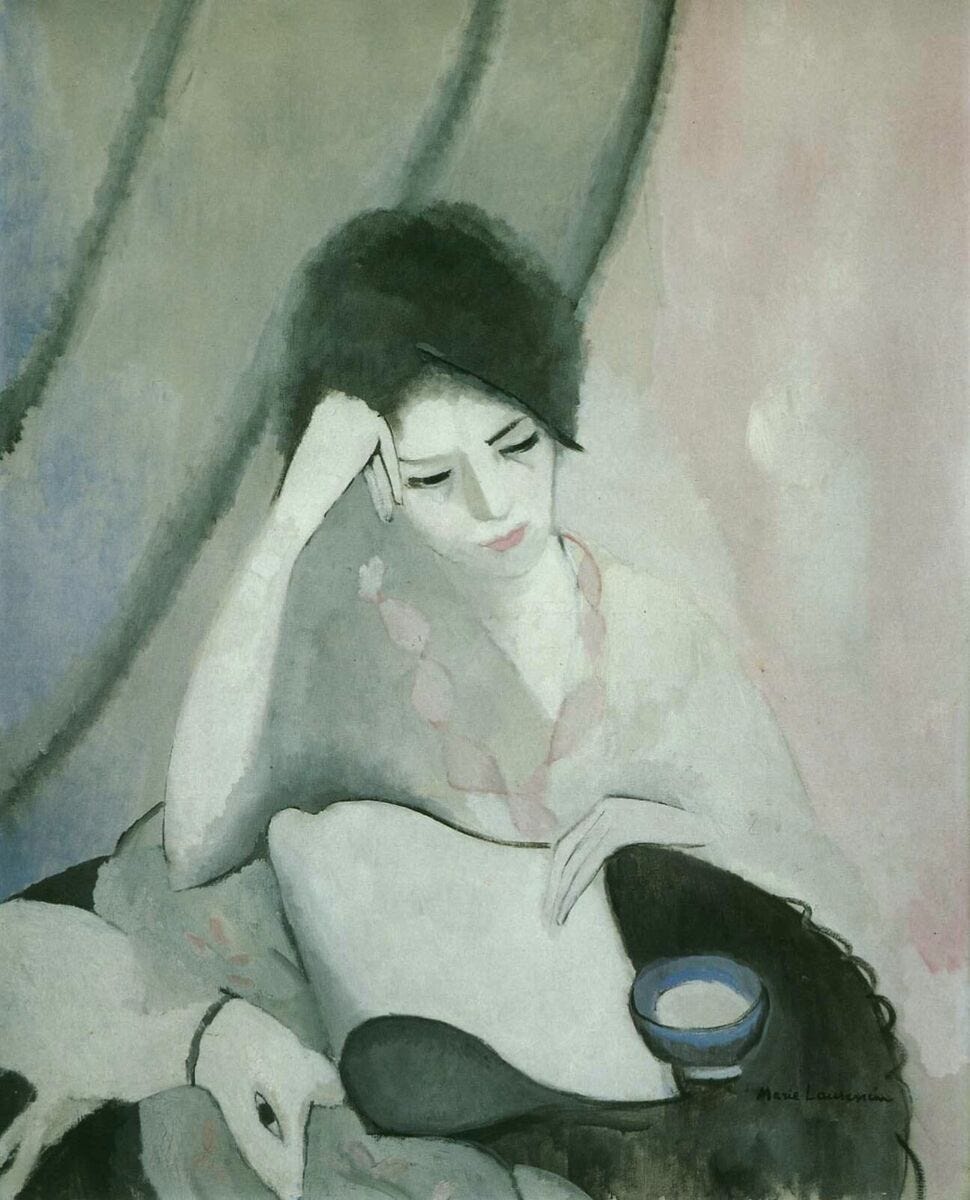

Billy and Francis don’t seek to destroy their existing lives. Rather, they’re drawn to each other because they offer something specific the other cannot find elsewhere. For Francis, Billy is that “little light and dark,” the contrast that sharpens the edges of his world. It isn’t always clear what Billy gets from Francis, and though it’s hard to define his role in her life, it’s obvious that he’s an essential reprieve. With him, in many ways, she can simply be.

The Danger of the "Perfect Partner"

Colwin’s novel quietly but firmly rejects the notion of the perfect partner. Billy and Francis aren’t trying to replace their spouses or families; they’re searching for something more nebulous—a fulfillment that transcends the boundaries of their prescribed lives. This is not to justify their choices but to acknowledge their humanity. Why should we expect one person to meet every emotional, intellectual, and physical need? And why do we judge those who seek fulfillment beyond the confines of traditional relationships?

This question feels particularly urgent in today’s culture, where we continue to fetishize romantic love as the ultimate goal. Dating apps promise us compatibility down to the decimal. Social media floods us with images of perfect couples, curated to suggest that true happiness lies in the arms of someone else. Yet Colwin reminds us that love is rarely that simple. The beauty of her work lies in its refusal to glorify or condemn. Instead, she illuminates the ways we fumble toward connection, often imperfectly, sometimes selfishly, but always in search of something real.

Light, Dark, and the Gray In-Between

Francis’s yearning for light and dark, for the clarity of life’s contrasts, feels almost universal. We are drawn to what unsettles us, what excites and frightens us in equal measure. But Colwin is careful to avoid portraying Billy and Francis’s affair as a solution to their discontent. Their relationship is a reprieve, not an answer. It is beautiful and flawed, tender and transient.

By resisting easy moral conclusions, Colwin leaves space for the reader to sit with discomfort. Perhaps that’s why Another Marvelous Thing still feels so resonant today. It asks us to confront our assumptions about love and fidelity, about the roles we assign to ourselves and others in relationships. It asks whether we’re chasing an ideal that doesn’t exist, and whether, in doing so, we’re setting ourselves up for disappointment.

The Freedom to Want More

Billy and Francis’s affair might not align with societal norms, but it’s an honest expression of their desires. They are not villainous or selfish in the way we might expect. They are, simply, human. Colwin shows us the joy and sadness of their connection, the fleeting nature of what they find in each other.

Perhaps what makes the book so striking is its refusal to judge. It doesn’t tell us whether Billy and Francis are right or wrong. It doesn’t ask us to condone their choices. Instead, it asks us to look inward. Why do we demand so much from love? Why do we cling to the idea that one person can be everything?

Another Marvelous Thing is not a manifesto for infidelity, nor is it an argument against it. It is, rather, a reflection of life’s complexities. In the interplay of light and dark, Colwin captures something essential about human connection: it’s never just one thing. It’s love and longing, fulfillment and disappointment, stability and risk. To deny ourselves the full spectrum is to deny our humanity.

As Francis gazes at Billy, seeing both the light and dark she brings to his life, we are reminded that love is rarely simple. And maybe that’s okay.